Gambler Video

Viewing video requires the latest version of Adobe's Flash Player

A Clark County jury awarded local gambler Chad Johnson $250,000 last month after he filed a civil lawsuit against the Imperial Palace alleging assault, battery and false imprisonment. After he complained about a faulty slot machine, there was an altercation between security guards and Johnson. This video shows the incident.

Archives

- Gambler wins $250,000 lawsuit against Imperial Palace (5-25-2011)

- Las Vegas ‘advantage gambler’ loses appeal against Mirage, state (5-5-2011)

- Hard Rock Hotel guest files suit alleging assault, defamation (12-27-2010)

- Pro gambler settles Imperial Palace claim for $65,000 (4-13-2010)

- Private counseling plan was no secret (9-25-2009)

- Cops knew of counseling service (9-19-2009)

- District judge who endorsed counseling service could face investigation, expert says (9-19-2009)

- Cops raid firm accused of extortion (9-16-2009)

- Familiar face in awkward place in court (9-15-2009)

VEGAS INC coverage

In a downtown Las Vegas office, CD cases are stacked haphazardly, like an exhaustive, meticulously labeled music collection. These aren’t albums but rather, casino surveillance footage showing altercations between customers and casino security.

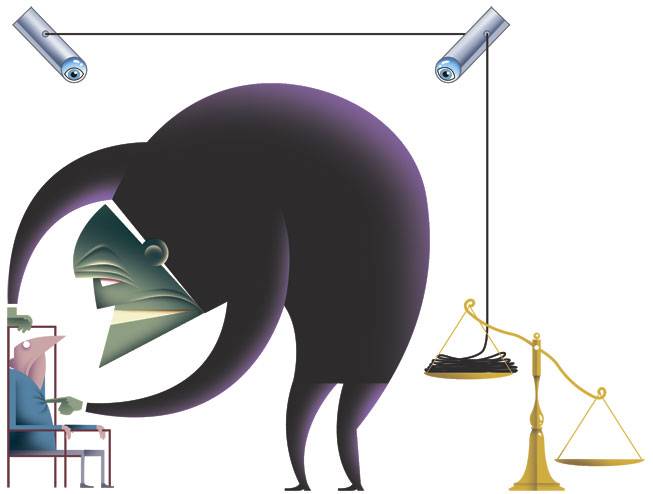

This is a town where people are wary of making enemies of casinos, yet Bob Nersesian has made a career out of suing casinos and their security for assault and battery on behalf of customers. Financing his trade is a mother lode of video captured on DVD — evidence casinos are required to keep in the wake of pending lawsuits.

Business in the downturn has been good for Nersesian, who chooses cases believed to have damaging video evidence. He and law partner Thea Sankiewicz have about 50 such cases in progress at any one time and file a new lawsuit about once every two weeks. That’s pretty much the same as a decade ago, before growing publicity about such cases and their costs for casinos.

“I get about three calls a day on this,” he said. “I’m so busy I’m turning people away.”

Most of Nersesian’s cases are settled confidentially with casinos. The few that go to trial almost always end badly for casinos that can be found liable for assault, battery and unlawful detention, with judgments in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. In one case, a jury years ago found a casino in the clear, he said.

His track record has prompted invitations to casino conferences, where he has advised managers on how to avoid such lawsuits.

The DVDs show a darker side of Las Vegas’ glamorous resorts little known outside courtrooms and a small circle of security experts.

Near the top of the pile is a video starring Angelo Stamis, owner of Jerry’s Nugget, who approaches a gambler, demands ID and tells the customer to leave. The video shows the gambler leaving, but not before swearing at Stamis, who then grabs the gambler, Thomas Robertson, by the arm while a guard handcuffs him. North Las Vegas police arrested Robertson for supposedly refusing to leave.

North Las Vegas Municipal Court dropped the charges in November, saying Robertson had committed no crime and the casino had no right to evict him.

Robertson’s lawsuit against the casino is pending. Jerry’s Nugget representatives couldn’t be reached for comment.

Surveillance footage from other casinos shows customers being nabbed and detained by security guards in offices where the patrons are threatened with arrest should they return to the casino. Some DVDs are no longer than a few minutes, while others contain several hours of footage.

It’s a far cry from the days casino bosses were known to beat undesirables and toss them in the street — or dump them in the desert.

Still, they hint at an earlier time when force was the preferred method for dealing with unwanted customers.

Nersesian and other critics of casino security call it a culture of thuggery and intimidation by poorly trained security guards. Police are inclined to believe that a handcuffed patron has committed a crime rather than suspect the customer was improperly arrested, they say.

“This is a pattern of behavior that’s been going on for more than 25 years,” Nersesian said. “We know better, as Americans, not to take someone and detain them in a room.”

Nevada law defines battery a “any willful and unlawful use of force or violence upon the person of another” and assault as “unlawfully attempting to use physical force against another person” or “intentionally placing another person in reasonable apprehension of immediate bodily harm.” Both are misdemeanors, although battery resulting in “substantial bodily harm” is a felony that carries a minimum prison term of one year. False imprisonment, “confinement or detention without sufficient legal authority,” is a gross misdemeanor.

Critics fault casinos for failing to adequately train security guards in the kind of verbal judo police officers use to talk to suspects in tense situations. Instead, they say, security guards too frequently seize unruly or unwanted customers rather than let them leave the premises or immediately call police to have patrons arrested.

The DVD footage shows security officers obtaining ID from handcuffed customers and taking pictures of them for their own records. Some, like Robertson, aren’t criminals or under suspicion for crimes but rather, skilled gamblers known to win money from the casino. Casinos are entitled to evict unwanted customers and that, notwithstanding the contrarian decision by the North Las Vegas court, Nevada law entitles them to arrest those who violate trespass warnings.

Caesars Entertainment spokesman Gary Thompson said the company has a right to refuse service by escorting a patron out of the casino. The company also has a right to detain someone if it has reason to believe that illegal activity, such as cheating a game, has occurred, he added.

In April, Imperial Palace was found liable for assault, battery and false imprisonment in its handling of a gambler who had complained about a faulty slot machine, resulting in a $250,000 judgment against the casino. The security chief, who no longer works there, had previously been found liable in an assault case stemming from a 2001 incident at the New Frontier that resulted in a judgment of $110,000 against that casino. Thompson declined to comment on the suit.

Lawsuits can be costly and time consuming, Thompson said.

“We want to ensure that our guests have a good time in a safe environment. If we see any behavior that’s observed or reported that’s offensive to guests or unsafe for employees or guests, we have a responsibility to intervene.”

The company’s security forces receive periodic training to ensure they are doing their jobs properly, he said.

One expert witness who has served plaintiffs and defendants in casino assault cases says training programs for casino security guards are woefully lacking in Las Vegas.

“You don’t see these kinds of cases in places like Tunica and Biloxi (Mississippi). Most are in Nevada and Atlantic City and that says something — it says that something’s wrong,” said Fred Del Marva, an Arizona-based security instructor and private investigator.

Employee manuals for security differ little from casino to casino as they tend to be generically written, without specific examples on how to handle, say, a cursing gambler, Del Marva said.

“(Security) really doesn’t have the patience to take verbal abuse from someone he’s asking to leave. Rather than providing the higher standard of care that’s required when you’re dealing with a guy who is drunk or belligerent, they act on adrenaline and treat customers like thugs,” he said.

Security guards have no more right to arrest a customer than any other citizen in that they can make an arrest if they see a crime occurring. Most assault cases aren’t about criminal activity, but rather, are a display of force by security guards who view themselves as authority figures with pseudo-police powers, he said.

“Instead of saying, ‘Will you follow me to the exit? No? Fine, I’ll call (the police),’ they want to show their authority.”

Mike Bryant, president of the Las Vegas Security Chiefs Association and director of security at South Point, declined to comment on casino security policies in general, saying each casino follows its own procedures.

Casinos aren’t putting their guards through sensitivity training, casino consultant Bill Zender said.

As a casino manager in the 1990s, Zender warned security of grabbing unwanted gamblers and hauling them forcibly out of the casino.

“You can’t put your hands on people or hold people for no reason, which is a form of kidnapping,” he said. “If he says ‘I’m leaving’ you can’t drag him in and take his picture.”

Nevada regulators say they have not witnessed a rash of wrongful behavior that would warrant fines or, worse yet, suspended casino licenses.

“If a security guard who has had a bad day hauls off and hits someone, it’s hard to hold the casino accountable,” Control Board Chairman Mark Lipparelli said. “We would look at that incident in context, like whether they fired the guy and whether this was one bad guard or a problem department. If there’s a pattern at a casino where they are hiring people without background checks or are tolerating the wrong behavior, that’s a problem and we want to know about it.”

The Control Board has recently cracked down on nightclubs for allowing reckless behavior, including roughing up customers. Two clubs in particular terminated several security guards and trained others in response to the board’s concerns, Lipparelli said, declining to name the clubs.

Metro Police is reluctant to file police reports against casino security for assault and battery, preferring to view such crimes as civil disputes between casinos and their customers, Nersesian said.

Metro spokeswoman Laura Meltzer said police follow simple protocol when dealing with any potential victim — take a report, pass the case on to an investigator and rely on the victim to press charges and follow up with detectives. Some victims don’t follow up, or there may be a lack of convincing evidence, she said.

“We’re not going to deny someone a report who has been the victim of a crime,” she said. A victim may be told to return after sobering up, or the incident may simply not meet the definition of a crime, she added.

Metro isn’t aware of a pattern of security abuses in Las Vegas casinos, although there are many kinds of casino requests for law enforcement that tracking the incidents in which patrons complain of battery is difficult, Meltzer said.

Claims of assault by security guards are common in entertainment districts across the country known for their party scene and free-flowing booze, said Bill Sousa, a UNLV criminal justice professor.

In higher risk tourist zones such as Las Vegas, police should be able to help security guards avoid altercations as part of the overall goal of any law enforcement agency to lower crime statistics, he said.

Critics cite a too-close relationship between police and casino security for the lack of criminal charges against guards.

Police “seem to fail to do their own investigations...they kind of act as an arm of casino security,” said Allen Lichtenstein, American Civil Liberties Union Nevada counsel.

Del Marva said “they don’t want problems with the casinos, with which they all have connections. The casinos are going to do what they’re going to do without police interference.”

Things were different for Imperial Palace gambler Chad Johnson. The day after his 2008 altercation with security, Johnson went to Metro to show police his bruised body. Police referred the case to the district attorney, which filed a misdemeanor battery charge against the security manager. The case against the manager, who paid $351 in restitution and attended an anger management course, was dismissed in 2009. It’s the first of more than 100 assault cases Nersesian has handled since 1995 to yield criminal charges against a casino employee.

About two dozen of those cases have resulted in jury verdicts against casinos for illegal assault or arrest.

“Not once have I seen police or gaming (regulators) walk into a scene with security and say, ‘Thanks for calling us, but you guys messed up,’ ” Nersesian said. “It’s their responsibility to investigate unsuitable practices but apparently it’s not an unsuitable practice to beat on people.”

“We don’t want our licensees out there assaulting patrons,” said David Salas, deputy chief of the Control Board’s enforcement division. “There’s anecdotal evidence that it occurs. But I would refute that it’s a widespread problem.”