COYOTE SPRINGS — When Kevin Tiffin first came to play golf in this remote stretch of mountain-framed desert — with pretty much nothing around besides the 18-hole course — he figured it was a bad joke.

“I thought we were going to an Alfred Hitchcock movie,” he said.

Donnie Luper and Manjinder Lalh came here last month to hit the links while visiting Las Vegas for a convention. The course is about an hour’s drive north of the Strip, and after passing the edge of town, it’s a lonely trek.

“We wondered, driving out here, whether we were going the wrong way,” Luper said.

Coyote Springs, launched by former powerhouse lobbyist and current prison inmate Harvey Whittemore, has a golf course — a highly ranked one at that — and little else. But it was supposed to be a 43,000-acre community, a city built from scratch in the middle of nowhere during Southern Nevada’s go-go years.

Whittemore declared his project “a community for the new millennium,” a place without “the negatives of traffic and crime found in Las Vegas.”

“It’s going to be a full city,” he said.

His plans fizzled with the recession and bitter lawsuits between him and his partners that read like a crime thriller. They flung accusations of rampant embezzlement, death threats, secret stacks of $100 bills, and a “very ominous and burly” thug who emptied the Whittemores’ safe of jewelry and cash.

But now, years after the massive project fell by the wayside, Coyote Springs’ developers are trying to revive it.

Whittemore’s former partners, the Seeno family of the San Francisco Bay Area, recently gained full control of the property through a legal settlement and aim to build the long-stalled community.

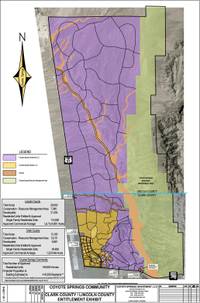

The group has approvals to build as many as 159,600 homes and more than 10,000 acres of commercial property. If all goes as planned, it would easily take 50 or 60 years, if not longer, to complete the project, “barring some sort of crazy boom” that no one expects, general counsel Emilia Cargill said.

Coyote Springs — nearly twice the size of Las Vegas’ largest master-planned community, Summerlin — has been on the drawing board since at least 2000, but little is built.

Coyote Springs

There are no homes — dozens of empty housing pads line the golf course — and when asked whether roads have been built, Cargill said that’s “kind of a trick question.” Most haven’t been paved yet.

The golf shop and players’ lounge are in temporary trailers, and north of the golf course, an abandoned, partially built community center sits off U.S. 93.

“Why would you want to live out here?” said Lalh, visiting from Edmonton, Alberta. “You’re so far from everything.”

Yet more than $100 million has been spent on Coyote Springs, Cargill said, and the project has water rights and electricity. Before the Seenos try selling land to homebuilders, they want to complete utility work, including the partially built water-treatment and wastewater-treatment plants, she said.

According to Cargill, they hope to have homes being built by early 2017.

The project site, she said, is “not that far” from Las Vegas and is “a true suburb” of the city.

“People ask (if we are) ever gonna build homes. And of course, our answer’s ‘Yes, that’s the intent — to build homes, build a city,’” said Michael Ghiorso, director of operations for Coyote Springs Golf Club. “It’s always been that.”

Time will tell whether people are willing to move here and help build that dream — or whether Coyote Springs will remain little more than a ghost-town golf course.

“Let’s put it this way,” said homebuilder Kent Lay, Las Vegas division president for Woodside Homes. “I’m not standing in line to buy property there, and I wouldn’t want to be the first one in line to do it.”

•••

In summer 2006, politicians, Whittemore and other bigwigs gathered under a tent here for a news conference. They cheered the project and the jobs it would create, and congratulated one another on getting things up and running.

Federal regulators normally are “throwing spears” at people who want to build something like Coyote Springs, Sen. Harry Reid said at the event.

“But this here truly is a lovefest,” said Reid, who reportedly organized the gathering.

By then, Whittemore’s lobbying powers had faded — he had a falling-out with casino companies a few years earlier and had turned his focus to Coyote Springs — but his name and presence still carried big weight in politics. Moreover, Las Vegas’ real estate market was booming, with soaring land and housing prices and rapid construction.

In the search for large, low-priced tracts of dirt, developers drew up plans for cheaper housing about an hour away in such places as Pahrump and Mesquite. For many residents, moving to the fringes may have seemed like the only way to get an affordable house in the Las Vegas area.

Eventually, the bubble burst and the economy crashed. Coyote Springs fit with the boom years, real estate pros say, but the market is much different today — namely, slower and cheaper.

Home values are well below boom-era levels, and almost no one, if anyone, complains of being priced out of town. There is plenty of land in and around Las Vegas, and it’s selling for much-cheaper prices than last decade. Gas prices are higher, as well, making long commutes costly.

If the valley were booming again and there were a shortage of land, “I could see something happening” in Coyote Springs, said Scott Beaudry, owner of housing brokerage Universal Realty. But that’s not the case.

Also, he noted, people increasingly want to live in urban areas, near retail, recreation and work, not in outposts that require lots of driving every day.

“I just don’t see it right now,” Beaudry said of Coyote Springs. “I really, really don’t.”

Coyote Springs might appeal to retirees or aging empty-nesters, real estate executives said. But such buyers are unlikely to move here unless retail, medical care and other services are in place first.

Moreover, home prices would have to be far higher in Las Vegas to persuade buyers to take a hefty commute in exchange for cheaper housing, RCG Economics founder John Restrepo said.

“We’re not at that point yet,” he said.

Even if Coyote Springs offered steep discounts, buyers can already get those savings in older neighborhoods in Las Vegas, homebuilder Wayne Laska said.

Laska, owner of StoryBook Homes, said Coyote Springs is a “really risky venture” and “an ill-conceived project.” And he isn’t sure the Seenos can price their land low enough for him to buy.

“I’m not sure if (they) gave us land we’d build out there, to be honest with you,” he said.

•••

Despite its size and scope, Coyote Springs in some ways is not unique. Southern Nevada is an anything-goes real estate market where big, risky projects get pitched all the time.

Of course, plenty of them flop. During the recession, the valley was littered with abandoned, partially built condo buildings, megaresorts, housing tracts and other projects, and many other plans died on the drawing board.

Still, big projects once viewed as being in the middle of nowhere have found success.

When developers started building The Lakes, for instance, in the mid-1980s, Janet Carpenter couldn’t understand why anyone would want to live “way out there” at the housing and commercial project built around a man-made lake in what was then open desert. Five years later, she bought a house there.

The Lakes, however, is just seven miles west of the Strip, whereas Coyote Springs is about 60 miles away. But Carpenter, a broker with Signature Real Estate Group, noted that some people don’t mind a long commute.

She once sold a house for a UPS driver who was moving from the valley to Mesquite, about 80 miles northeast of Las Vegas. He planned to keep working in Las Vegas, which Carpenter thought was “the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard.”

“But I’ve seen it happen,” she said.

Home Builders Research founder Dennis Smith once thought Coyote Springs would do well but now dismisses it as far-fetched. It’s a great place to live “if you’re hiding from somebody,” he said, and at 64 years old, he doesn’t expect “to see anything out there before I’m dead.”

Still, he said people in the 1990s laughed at developer Jim Rhodes for launching the 1,300-acre Rhodes Ranch on the outskirts of town, about 10 miles southwest of the Strip.

“There are people with money who do some silly things sometimes,” Smith said, “and then they turn out to be visionaries.”

•••

Coyote Springs, straddling the Clark and Lincoln county lines, isn’t some lush oasis that Whittemore stumbled upon and other developers overlooked.

“It amazes me that (he’s) interested in that area,” a Bureau of Land Management official said in 2000, after Whittemore laid out his plans. “There’s no lake, no fishing. There’s really nothing there.”

Previous owners figured the site was ideal for building and testing missile engines. Aerojet-General Corp. acquired the property in 1988 in a land swap with the U.S. government and sought to build a facility.

The plans never materialized, and Aerojet sold the site in 1998 to two influential Northern Nevadans: lobbyist Whittemore and partner David Loeb, a real estate developer and co-founder of mortgage lender Countrywide Financial Corp.

Despite the back-slapping at the news conference years later, not everyone welcomed the planned city. Environmentalists in particular criticized the project, saying it would harm sensitive areas and that it typified leapfrog development. Activist groups sued to block it.

The Environmental Protection Agency, however, gave Whittemore an award.

His project, the EPA said in 2006, was “committed to preserving aquatic resources” and was “a model for environmentally sensitive development in the arid West.”

“You’re kidding me,” the director of the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada said at the time. “I don’t know why anyone would get an award for plopping 80,000 homes down in the middle of the desert. Maybe they’ll give an award to Yucca Mountain next,” he said of the proposed nuclear-waste dump.

Loeb died in 2003, and afterward, Whittemore brought in Bay Area homebuilder Tom Seeno as a partner. Seeno, whose family has owned stakes in Nevada casinos, acquired 50 percent ownership of Whittemore’s development company, according to court records.

In 2004, the duo signed Pardee Homes as Coyote Springs’ lead builder. The company agreed to buy 2,000 acres, slated for about 7,000 homes, and had an option to buy an additional 13,000 acres, reports said.

Court filings say Pardee paid more than $100 million for land here and had an option to buy the whole project site for $1.2 billion.

“I think Las Vegas is moving closer to Coyote every day,” Whittemore said when the deal was announced. “You’re only 50 minutes away. That’s nothing. You look at the choices people are making. Pahrump? Is that drive easy?”

Seeno’s brother Albert Seeno Jr. also invested, buying one-third of the development company, court records show.

With all the government approvals needed to build, Whittemore drew scrutiny over his deep political connections. But, he said in 2006, he’d always face some opposition because of his lobbying background and, he said, his successful career.

“I think people are a little bit jealous,” he said. “I am very blessed. I am the luckiest guy in America.”

•••

By spring 2007, with cracks appearing in Las Vegas’ housing market, there were reports that Coyote Springs was foundering.

“Not at all. I don’t know where that comes from,” Klif Andrews, Las Vegas division president for Pardee, said at the time.

There were delays with utility and other work, Whittemore said then, but it “doesn’t have anything to do with the market at all.”

In late 2008 — a few months after Lehman Brothers collapsed and with the financial crisis in full swing — Whittemore’s group expected home construction to start in 2010.

Instead, as the economy crumbled, executives sued one another and Coyote Springs ground to a halt.

In 2011, the developers sued Pardee, alleging the company had, among other things, failed to start “vertical construction” of the golf clubhouse and complete site work for utilities.

In 2012, the Seenos, through various limited liability companies, sued Whittemore and his wife, Annette, alleging the embezzlement of “tens of millions of dollars.”

According to the suit, Harvey Whittemore “confessed” that company money was used for, among other things, his daughter’s wedding; political fundraisers and parties; box seats for Reno Aces minor-league baseball games; high-end stereo equipment; and loans to friends.

Moreover, he allegedly “withdrew hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash” from the company. At Whittemore’s instruction, the lawsuit claimed, employees always kept between $5,000 and $10,000, in $100 bills, in a safe in the office. Whittemore yanked out $315,000 in 2006 alone, the Seenos claimed.

Less than a week after the suit was filed, the Whittemores struck back, suing the Seeno brothers and Albert’s son Albert Seeno III.

After the economy tanked, Albert Jr. “became disgruntled about his investment” and “started falsely accusing” Harvey Whittemore of financial crimes, the suit alleges.

At a summer 2010 meeting at the Peppermill resort in Reno, according to the lawsuit, Albert Jr. threatened to go to the FBI; threatened to “personally bring down every member” of Nevada’s political machine; asked Whittemore whether he believed in God and told him to “gather his flock on Sunday and pray”; and threatened the lives of Whittemore and his family.

The Seenos also allegedly sent employees to the Whittemores’ homes “to intimidate them and force them to give up” jewelry, art, cars and other assets.

One time, the lawsuit claimed, “a large, very ominous and burly man named ‘Ray’ demanded that Mr. Whittemore open a safe in the house.” Apparently joined by other goons, Ray told Whittemore they only wanted to see what was inside, but he “dumped everything in the safe into a bag and took it with him.”

Meanwhile, a few months after he sued the Seenos, a federal grand jury indicted Whittemore on charges that he funneled illegal campaign donations to a member of Congress — later identified as Reid — and lied to FBI agents about it. A jury in 2013 found Whittemore guilty on three of four counts, and a judge sentenced him to two years in prison and fined him $100,000.

Litigation about Coyote Springs eventually was resolved. The Seenos bought out Whittemore’s stake in the project a few years ago in a “very, very confidential” settlement, general counsel Cargill said, and the Seenos in June reacquired about 2,600 acres that Pardee previously owned.

Whittemore, now 62, is incarcerated in Lompoc, Calif., and is scheduled to be released May 2, 2016, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

The Sun mailed a letter to him last month requesting to talk about Coyote Springs. No response was received as of publication deadline.

Efforts to speak with attorneys who represented the Whittemores, the Seenos and Pardee, as well as with the Seenos themselves and Pardee’s Andrews were unsuccessful Thursday.

Cargill, for one, says her group is focused on the future, and she didn’t want the infighting “dredged up.”

“That’s a part of the past,” she said.

•••

Coyote Springs Golf Club isn’t much of a club — for one thing, there’s no clubhouse — but it does have one of the best golf courses in Southern Nevada.

The par-72 course, designed by golf legend Jack Nicklaus, opened in 2008, the first of what was supposed to be a dozen or so courses at Coyote Springs. Golfweek for years named it one of the top 100 residential courses, and Golf Digest in 2011 ranked it one of America’s top 100 public courses (it tied for 95th).

Driving around the course recently, director of golf Karl Larcom said the course is kept in great shape and is tough to play, with rolling fairways and deep bunkers.

Tiffin, the golfer, said it’s in “pristine condition.”

“Honestly, it’s unbelievable,” Colorado property manager Barry Schafer said between strokes during a recent visit here. He was on a golfing vacation with his wife and friends, including Tiffin. “This is by far the nicest we’ve played.”

Golfers often wonder why the course is in the middle of nowhere, asking staff members why it is where it is and whether they really drive here every day for work.

“Those are the two questions that we get 100 times a day,” said Larcom, who lives in Henderson and has a 67-mile commute.

For his part, Schafer doesn’t care that Coyote Springs is house-less. He comes to play golf.

“Every time we’ve played here,” he said, “it’s the same: perfect.”

Staff librarian Rebecca Clifford-Cruz contributed research to this report.